import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from matplotlib.animation import FuncAnimation

from IPython.display import HTML

# Trajectory data (projectile motion measurements)

tdata = np.array([0, 0.016666667, 0.033333333, 0.05, 0.066666667, 0.083333333, 0.1,

0.116666667, 0.133333333, 0.15, 0.166666667, 0.183333333, 0.2,

0.216666667, 0.233333333, 0.25, 0.266666667, 0.283333333, 0.3,

0.316666667, 0.333333333, 0.35, 0.366666667, 0.383333333, 0.4,

0.416666667, 0.433333333, 0.45, 0.466666667, 0.483333333, 0.5,

0.516666667, 0.533333333, 0.55, 0.566666667, 0.583333333, 0.6,

0.616666667, 0.633333333, 0.65, 0.666666667, 0.683333333])

xdata = np.array([0, 0.022727273, 0.045454545, 0.068181818, 0.090909091, 0.113636364,

0.136363636, 0.159090909, 0.181818182, 0.204545455, 0.227272727, 0.25,

0.272727273, 0.295454545, 0.318181818, 0.340909091, 0.363636364,

0.386363636, 0.409090909, 0.431818182, 0.454545455, 0.477272727, 0.5,

0.522727273, 0.545454545, 0.568181818, 0.590909091, 0.613636364,

0.636363636, 0.659090909, 0.681818182, 0.704545455, 0.727272727, 0.75,

0.772727273, 0.795454545, 0.818181818, 0.840909091, 0.863636364,

0.886363636, 0.909090909, 0.931818182])

ydata = np.array([0, 0.055454293, 0.108180808, 0.158179545, 0.205450505, 0.249993687,

0.291809091, 0.330896717, 0.367256566, 0.400888636, 0.431792929,

0.459969444, 0.485418182, 0.508139141, 0.528132323, 0.545397727,

0.559935354, 0.571745202, 0.580827273, 0.587181566, 0.590808081,

0.591706818, 0.589877778, 0.58532096, 0.578036364, 0.56802399,

0.555283838, 0.539815909, 0.521620202, 0.500696717, 0.477045455,

0.450666414, 0.421559596, 0.389725, 0.355162626, 0.317872475,

0.277854545, 0.235108838, 0.189635354, 0.141434091, 0.090505051,

0.036848232])

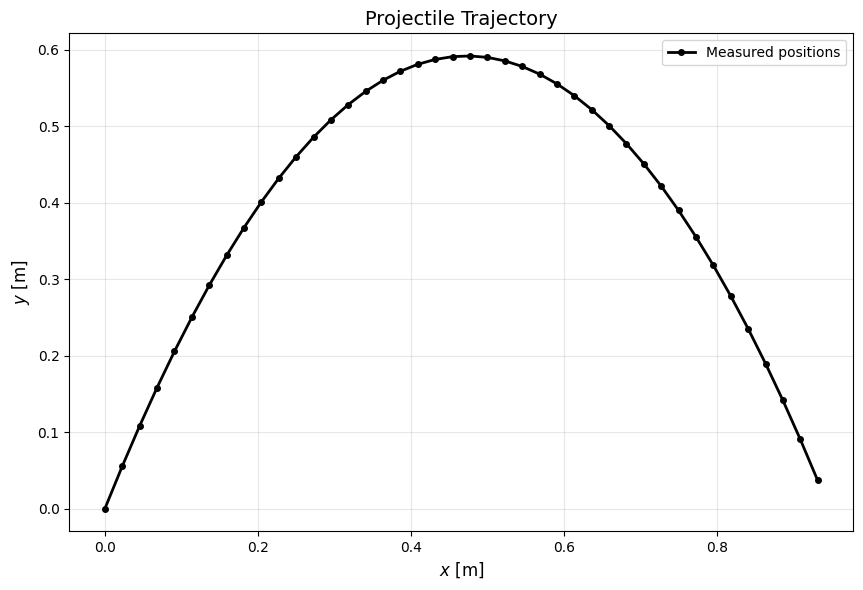

# Plot the trajectory

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 6))

ax.plot(xdata, ydata, 'ko-', linewidth=2, markersize=4, label='Measured positions')

ax.set_xlabel('$x$ [m]', fontsize=12)

ax.set_ylabel('$y$ [m]', fontsize=12)

ax.set_title('Projectile Trajectory', fontsize=14)

ax.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

ax.set_aspect('equal', adjustable='box')

ax.legend()

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()